text by Yulia Tikhomirova • June, 2023

For Italian version >> click here

The anti-monumental operation is one of the main directions TIST approaches in its work addressing it in two complementary but opposing manners:

- the destruction of an object-monument through collective use and

- the construction of a lieu de mémoire through collective commitment.

The first artistic device used by TIST for the anti-monumental practice was implemented by Michele Liparesi in 2016 in Florence. At times, still a student from the sculpture department of Fine Arts Academy, Liparesi observed the complete conversion of the city into an open-air museum at the service of tourists. As the artist claimed:

For young artists, there was simply no physical space left to use for any kind of activity in the urban space. The city was overwhelmed by monuments cordoned off, guarded, and prohibited from touching or using in any way. At the same time, the rent prices were growing dizzyingly, forcing students to move out to the periphery or to leave.

This emergency gave rise to the A Living Unit project. Liparesi constructed a device that looked like a typical eighteenth-century statue on a vigorously decorated pedestal, perfect for camouflaging in the decorum of any Florence square. The sculpture represented the artist himself, dressed according to the fashion of past centuries, looking from up to down at the passers-by.

Nonetheless, it was the pedestal to be the central part of the operation: the 2- meters-high and 1-meter-wide booth appeared to be a classic basement embellished with plaster moldings. By approaching it, however, the viewer realized that the whole ensemble was made of recycled wood and reused utensils and could be, at best, considered a prototype for an actual monument yet to come. Moreover, the object was on wheels, so the artist could effortlessly push it around the streets despite its imposing size. The plaster decorations, in turn, represented genre scenes and inscriptions that gave precise instructions: all four sides of the monument were to open and utilize deconstructing, thus, the whole complex. Once dismantled, the (anti)monumental structure offered a functional kitchen, a table with footstools, a desk with an armchair, bookshelves, and a bed–a complete living unit for a student or a citizen who had faced the housing crisis.

In 2021, after the lockdown was eased, TIST’s members employed A Living Unit to address a new emergency: the fear of physicality and the long-lasting consequences this fear produced on the social relationships between people in the urban context. Liparesi’s prototype was freed from the sculpture on top, and the artists have focused on the further function of the device: to catalyze social encounters in the public space. The collective would push the A Living Unit around peripheral streets and make occasional stops offering coffee and wine to the passers-by. Based in the industrial outskirts of Bologna, in Rastignano, the collective was aware that the periphery residents would be the last category to return to everyday sociability after the lockdown, having already been deprived of social and cultural infrastructure even before the pandemic. Furthermore, the remoteness of marginal zones made it easier to transform an artistic gesture into a social participatory practice. Far from tourist sights, these areas were inhabited by residents who crossed the same streets and faced similar problems.

A Living Unit acted as an attraction or a pretext for physical encounters and dialogue, fulfilling the function of a missing social catalyst and bringing people together. Considering our paper’s main query, we affirm that the artistic device boosted the emergence of a temporary community, even if still not commemorative. In order to become the latter, a significant event that could influence the lives of the most, binding them to the same recollection, was necessary. As we write this article, in June 2023, the Rastignano’s inhabitants are living through the aftermath of the recent flood the Emilia Romagna region faced at the end of May. The cataclysm destroyed river embankments, roads and interrupted circulation in the zone, affecting everyday life. It is still early to assert the emergence of the recurrent remembrance practice related to this event; however, TIST’s members have already witnessed how the newly emerged community gets together to address the city council and demand responsibility for the mismanagement that caused such heavy consequences.

In 2022, TIST was invited to exhibit in the Public Space Museum of Bologna in the framework of the Urban Therapy Festival. Together with the A Living Union, TIST has exposed a conceptual prospect on the possible outcomes of the anti-monumental projects. The Possible Future Anti-Monument Units map had a futuristic impetus inspired partially by Archigram, an avant-garde British architectural group, and partially by the same post-pandemic social unease we mentioned above. Such units as Let’s Play, Stellarium for Two, or A Booth for a Forced Dialogue indulged in ironic and provocative forms rather than projected solutions to realize concretely.

At the end of the exhibition, which lasted one month, the Museum’s direction organized a street performance inviting TIST collective to repeat Rastignano’s experience and to bring the A Living Unit outside in the neighborhood. Although the event was successful in terms of audience and media coverage, we can not but underline that the very contest of the contemporary art milieu undermined the work’s concept. On the one hand, the art public perceived the anti-monument as a product of pure creativity, an art object free from any concrete emergency. On the other hand, even if curious, the local residents did not have enough time to engage with the project: a single event was insufficient for them to approach the device, let alone build connections. This experience proved to TIST’s members that “the Booth cannot exist but down the street. The places of art exhibit purely the shell while all the meaning is totally gone.”

Even if the Possible Future Anti-Monument Units were not thought up to be fabricated, one of them, the Sound Booth, turned out to be a fruitful idea for the teenagers of the small town near Vienna–Hollabrunn, where TIST’s members spent time in residency organized by the local curatorial team AIRInSilo, in March 2022. The artists were positively intrigued by the number of schools Hollabrunn offered and the flow of young people who passed through the town daily from neighboring communities. TIST found this situation particularly stimulating to work on and proposed a social anti-monument for the younger generation who suffered from the lack of cultural and leisure facilities. The Sound Booth has become the SoundInSilo Anti-monument for Hollabrunn, which is still ongoing work, currently at the planning stage. It visually recalls the early twentieth-century shed construction. Its design is inspired by the particular architecture of two silo storages one sees arriving at the town’s train station. The appearance fits the place from the urbanistic point of view while taking advantage of the triviality of its look that accentuates the surprise effect once the booth is opened.

The anti-monument will offer tables and seats and will be supplied with integrated sound speakers with a plug-in or Bluetooth system to facilitate connection to one’s phone. It will encourage the public sharing of music, radio, or audiobooks. SoundInSilo has a sliding roof to keep the sound located not to disturb the neighborhood and protect the listeners from sun or rain. For this project, TIST aims to involve the local community directly in the research, planning, and production activity. The artists intend to engage the students of the Hollabrunner Technik Leistungszentrums, one of the town’s leading technical high schools, in all phases of the work and cooperate with the local student radio station RadioYpsilon in communication plan and cultural program. This strategy aims to stimulate direct commitment and participation rather than simple curiosity. Besides the clear social function, which is to provide the younger people with a cultural facility that they will have to self-manage together, the idea is to leave the meaning of this operation as open as possible and to let it grow naturally through usage.

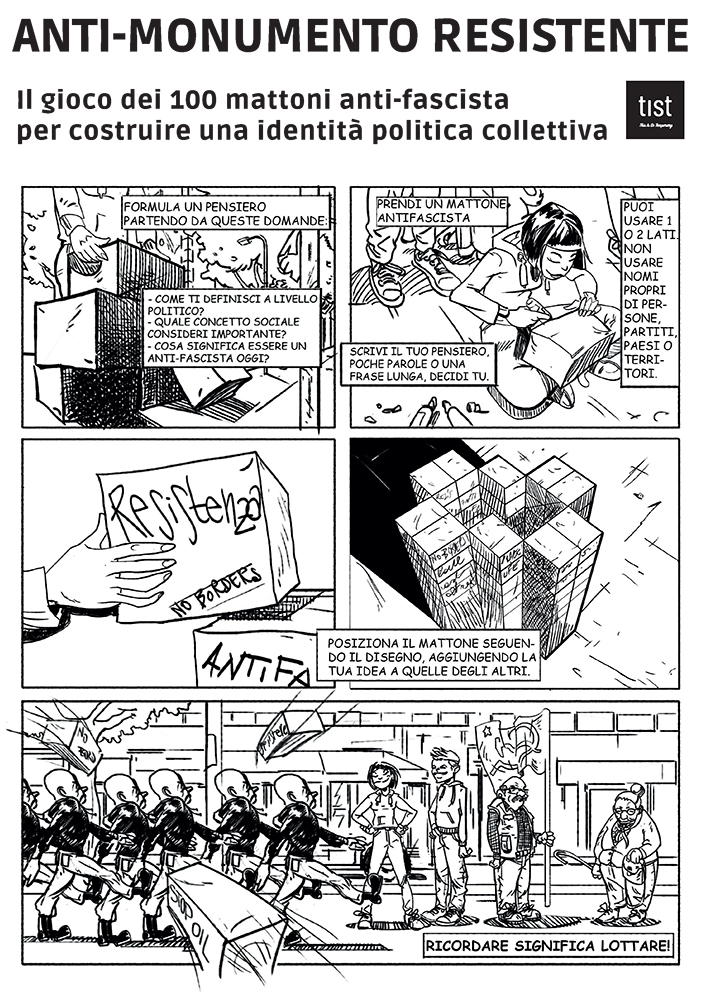

Another example of the anti-monumental practice by TIST has to do with the opposite process–the construction of a lieu de mémoire through collective commitment. According to the French historian Pierre Nora, places of memory are not necessarily restricted to specific locations. Everything that generates a symbolic meaning to which a given social group can relate be it a place, object, or period, can be called a place of memory.[1] The onset for such a procedure starts with identifying a community that already shares common values and spaces and offering it an idea that can structure a collective remembrance ritual. The Anti-fascist Anti-monument. Temporary But Resistant project was implemented in November 2022 in the framework of the street festival Oltre Il Ponte (Beyond the Bridge), dedicated to the anti-fascist resistance and the memory of the partisan battle that took place in 1944 in the Bolognina district of Bologna. The celebration of the Battle of the Bolognina coincided with a completely different kind of anniversary–the centenary of the march on Rome of the fascist militias, which ended with the takeover of power by Benito Mussolini. Thus, TIST’s members decided to address an urgent query–the significance of anti-fascism in the current circumstances–by letting citizens formulate their own social positions and elaborate a collective political identity.

The operation occurred on a busy street near the festival’s location and lasted one day, from early morning to late night. Here again, the artists had prepared art devices in advance and had conceived some initial rules that would catalyze a process, the result of which was left open. The passers-by were offered hundred cement-like cardboard blocks to write their reflections on. The blocks symbolized the bricks to be thrown at the infamous march. After writing a political message, the participants were invited to position the blocks one onto another to construct a new Temporary But Resistant monument.

This action had a playful character: the instructions were presented as a comix, and the written phrases looked like scribbles people leave spontaneously on the city walls. While personalizing one’s block, the inhabitants engaged in passionate discussions with each other on their political positions and on how efficient resistance to reactionary politics could be achieved. Moreover, the citizens established dialogues and polemics through written interventions by adding their thoughts to those already left by the others or by using arrows and visual connections directly on the walls of the anti-monument. In this case, the artists provided initial tools while leaving the process to the residents, who actively constructed the anti-fascist memorial they felt was lacking in the neighborhood.

In 2025, TIST took part in a new edition of the Oltre il Ponte festival, proposing the collective construction of a device to be carried during political demonstrations: Farò Corteo (literally: “I will march”) – A Tool for Collective Protest. The project functions as a gathering point for the positions, experiences, and reflections of protesters—an open tool that anyone can use to take the floor and articulate urgent issues to be discussed collectively. The structure of the device alludes to Vladimir Tatlin’s Monument to the Third International (1920). TIST drew inspiration from the foundational idea of that project: Tatlin was commissioned to imagine a construction capable of expressing the significance of a new historical horizon while avoiding traditional celebratory rhetoric.

However, unlike the avant-garde vision of the early twentieth century—where materials, form, and function were conceived as imposing symbols of modernity and progress—TIST works with precarious and reclaimed materials, the actual leftovers of modernity: non-functioning bicycles, rubber from tires, defective wooden slats, and scraps of metal mesh.

While critically engaging with Tatlin’s legacy, TIST invites a collective reimagining of new political futures in which the role of the human is no longer that of a conqueror of the world in the name of progress, but rather that of a responsible subject capable of caring for the surrounding environment. The project thus proposes the abandonment of a colonizing, anthropocentric position and calls for a distribution of power grounded in interdependence, followed by a redistribution of responsibility and care.

In conclusion, we will delineate the primary theoretical reflections behind the anti-monumental operation by TIST collective and make a synthetic comparison with the main features inherent in the traditional monumental practice, as traced by the scholars Quentin Stevens, Karen A. Franck, Ruth Fazakerley.[1]

- The first point to address here is the Subject. As mentioned above, a traditional monument is always dedicated to the only subject, be it a single personality, an event, or an abstract idea expressed in an affirmative tone. The anti-monuments by TIST are free from any pre-fabricated sense. They offer an idea of possible usage but do not directly indicate the sense behind the handling. Inhabitants create meaning by using the device and living it through. It is a stage for minimal actions, which can be comprehended through bodily interchanges in connection with others and the urban space.

- The second point refers to Form and Materials. A traditional monument needs an easily decipherable form in convention with a general taste of the specific time and place. The form should transmit power and sufficiency over the down-to-earth existence. The materials should be persistent and durable. The anti-monument, in turn, mimics familiar forms, taking inspiration from local architectural clichés and typical industrial structures. Once approached, it reveals its temporary nature and a prototype-like look. The materials are recycled and not meant to last.

- The third matter is linked to Site and Location. The site for a monument is an essential part of its significance and power. Traditional monuments are often prominent, set apart from everyday space, once and forever. Their elevation and immobility guarantee the correctness and eternity of their message. The anti-monuments are on wheels. They can be easily pushed around the city. They do not belong to a specific place or community. Their provisional nature is permanent. They oppose their nomadism to the correctness of immobility.

- The last issue concerns the notion of Visitor, Spectator, and User. The monuments demand from us just one sense–the sight. Most are designed to be viewed from a distance and down to up and pretend to put the spectator in awe. The anti-monument invites close, bodily encounters, transforming a visitor into a user, excluding the possibility of being a spectator, as soon as there is no discrete object for private introspection or an artist to perform a spectacle. The anti-monument can be activated only through physical relations and social care. The emotional affinity of its users with each other is the final aim of TIST’s practices.

Ultimately, we want to underline that the anti-monument project by TIST collective is a series of acts of appropriation of the public space that, for two decades, has been in drastic diminution in Italy due to the extractivist cultural politics that sees urban spaces merely as a source for investment and profit. TIST aims to renounce the celebratory aesthetics of commemoration and embellishment and to explore the humble position of a pedestal with the ultimate idea of activating social ties free from the monetary exchange or cultural policy dropped from above. While addressing the query of monumentality, TIST ascribes a temporary and open nature to the collective memory and attempts to rewrite forms, values, and experiences to trigger direct and unmediated dynamics in urban living. In the public space of our cities, remembrance is possible if it takes the form of a shared process and involves local agents rather than being consecrated to a monumental object.

[2] Quentin Stevens, Karen A. Franck, Ruth Fazakerley, “Counter-monuments: the Anti-monumental and the Dialogic.”

[1] Pierre Nora, “Between Memory and History: Les Lieux de Mémoire,” Representations, Special Issue: Memory and Counter-Memory, no. 26 (Spring 1989): 7–24.

This article originally was published by the the European Journal of Creative Practices in Cities and Landscapes (CPCL)

How to Cite:

Tikhomirova, Y. S. (2023). Counter-Non-Anti-Remembrance. The Anti-monumental Practices by TIST Collective. European Journal of Creative Practices in Cities and Landscapes, 6(2), 139–153. https://doi.org/10.6092/issn.2612-0496/17246